PILGRIMAGE TO MT. BANAHAW

I had always wanted to go on a pilgrimage to Mt. Banahaw, perhaps the country's premier indigenously Filipino pilgrimage site. However, the visit to the holy mountain remained elusive through the past more than fifty decades of my life. This desire intensified in the past decade during and after my UP studies and especially as I became more and more interested in knowing more about Filipino indigenous spirituality.

Finally, the opportunity arose with my sabbatical year. Since pilgrimage is somekind of a lietmotif of my sabbatical, I planned to include Mt. Banahaw in my itinerary. As I waited for the approval of visas to the countries I would go as pilgrim, I took off to the Quezon Province last August 20 to 22, 2006.

Thanks to the FMM Sisters' community in Sariaya who hosted me while I was in Sariaya, Quezon, the Mendoza family who provided me hospitality while I stayed in Sta. Lucia, Dolores, Quezon and my guides - Allan Abesamis and Pepay Mendoza - I had a wonderful pilgrimage in Mt. Banahaw.

A pilgrimage to Mt. Banahaw is a most unique spiritual experience as it combines a number of what ordinarily are opposing elements in today's society. Here the politics of a nationhood forged in revolution co-exist with the spirituality of liberation; the culture of folk Catholicism rests gently with the semiotics of indigenous mysticism. The symbols of a country that aspires towards lofty ideals of freedom and justice are at the same time the signs of a militant faith that seeks to build communities (samahans) of truth and righteousness.

There are places in the Philippines that every Filipino - if only all can afford to travel - should reach, visit, see and experience like Mt. Apo, the Cordillera's mountain terraces, Bohol's chocolate hills, Marawi's mosques by the lakeside, the Ati-atihan and Boracay, Lake Sebu, Palawan, Quiapo and Baclaran. Include in this list the mystical mountain of Mt. Banahaw.

I've been very lucky in terms of having visited many beautiful places, some of which bring the sojourner peace and joy because God's presence here is quite palpable. The days that I spent in Mt. Banahaw afforded such blessings.

(These are photos of Mt. Banahaw taken from various vantage points: from Kinabuhayan and Sta. Lucia in Dolores, from Lukban and from Tioang - all municipalities of Quezon. During my visit, which happened to be during the rainy season, there was always a veil on Mt. Banahaw's twin peaks.)

The peak of Mt. Banahaw can actually be climbed at its various sides, either from Sariaya, Dolores and other places around the mountain. Since my interest was to spend time with the samahans (literally associations but referred to by the anthropologist, P. Covar, as social movements) and go on a pamumwesto (walk through the sacred spots and do what a pilgrim is expected to do) I decided I would go up Mt. Banahaw through Dolores.

Since my base was Sariaya, Allan (my guide) and I travelled by bus to Tiaong, took the jeep to the poblacion of Dolores and a tricycle to Barangay Sta. Lucia which is part of Dolores. The travel took about two hours including waiting for the jeep to be filled with passengers. The travel is actually quite pleasant as the roads are cemented/asphalted all the way to Sta. Lucia.

When we arrived in Dolores, Allan and I first went inside the Catholic Church. At the main altar is the patron saint, Our Lady of Sorrows. It is not coincidental that Dolores (meaning sorrow) would have as its patron saint, our Lady as one of sorrows. But since I arrived in Sariaya, I noticed now popular this title of Mary is around this province. Is there a correlation between the sad history of this province (with its long series of revolts and massacres) and Mary's sorrows?

(The church, parochial school and the altar of the church in Dolores with Our Lady of Sorrows placed prominently above the altar)

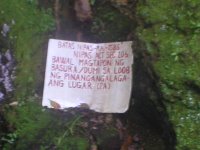

As soon as one steps down at Sta. Lucia, one immediately sees the sign - PATALASTAS ANG BANAHAW AY SARADO PA! (ANNOUNCEMENT BANAHAW IS STILL CLOSED!) It is prominently displayed near the Barangay Hall. The Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) and the Local Government have both declared some parts of Mt. Banahaw closed to mountaineers and pilgrims. The signboard indicates what these areas are on the side of Sariaya and the side of Dolores.

The closure of some parts of Mt. Banahaw - including the forested areas and the peaks - began on March 2004 and will last for five years. Through the past decades, there have been cutting of trees in these areas; mountaineers and trekkers have polluted these areas with the garbage that they brought along destorying the delicate eco-system of the mountain. Thus the ban for five years, much like what happened at Mt. Apo. Luckily, the places I wanted to see are not within the off-limits zone so my pilgrimage would not be affected by such ordinance.

However, when one is in Sta. Lucia one immediately notices the changes in the surroundings compared to the lowland areas of Quezon, including the poblacion of Dolores. Since Sta. Lucia is already more than half-way of Mt. Banahaw's more than 5,000 feet, this place is quite rustic and the various shades of green are greener here than in the lowlands. Around the area one is delighted to be confronted with scenic landscapes. And later that day as I woke around, there was even a small green snake that wiggled its way across the road. Lucky for me, I saw it before I stepped on it. (see photo)

Those familiar with the vast Philippine (and even foreign) literature written on Mt. Banahaw

(especially those written by the likes of Sturtevant, Covar, Ileto, Enriquez, Gorospe, Reyes, the Pamathalaan group) which traverse through the various social sciences to literary criticism to theology and spirituality think of Mt. Banahaw in terms of the samahans that go a long way to the Colorum before the turn of the century.

As of today, there are approximately a hundred of them peacefully co-existing with each other. The most famous ones as they have been subjects of various researches are the La Iglesia

del Ciudad Mistica de Dios and the Tres Personas Solo Dios. But there are also smaller samahans like the Bangon Bayan Banal (BBB), the Spiritual Filipino Catholic Church (with the statue of Rizal placed prominently in the frontyard), the Rosa Mistica, Nuestra Senora del Carmen, Samahan ni Tandang Sora and others. There is even a newly set-up Protestant denomination, the Jesus our Lord MBJM.

There are all kinds of signs to be read along the streets of Mt. Banahaw apart from the name of the different samahans. There are also the signs indicating where the various places are so the pilgrim knows which road to take. (The road to Sta. Lucia Falls is for the pamuestos and that of Kinabuhan goes all the way to the last samahan - the Tres Personas - before one reaches the off-limit zones).

There are also landmarks placed in strategic areas by the National Historical Commission. One informs the nationalist pilgrim that the hero Macario Sakay and his men retreated to this part of Mt. Banahaw during the height of their anti-colonial struggles. The confluence of these signs and symbols - political, cultural, religious - provides the unique character of Mt. Banahaw as it affirms the sojourner's citizenship, cultural identity and religiosity.

The signs and symbols in the villages located at various levels of Mt. Banahaw

show the convergences of the many facets of this locality that try to peacefully co-exist with one another.

show the convergences of the many facets of this locality that try to peacefully co-exist with one another.There are the religious signs along with ecological exhortations (Linis Labas - Clean outside) and religious aspirations (Linis Loob - Clean inside).

Across the Barangay Hall in Sta. Lucia is the headquarters of the military which suggests that Mt. Banahaw - like many mountain areas in the country - has its share of modern-day rebels, namely, the NPAs. Is this the case of history repeating itself? As there were rebels known as colorums (as well as tulisanes or those with sharp - tulis - arms) during the height of the Spanish colonial era, are there still rebels in this area until today?

The most ubiquitous, dominant and striking of symbols in Mt. Banahaw is the triangle with an eye. It appears everywhere from the landscape design to altar-shrines, above two pieces of cement on which the Ten Commandments are etched and the murals inside the different churches. Here its reference is, of course, God's all-seeing eye. (I wonder if anyone would think of Big Brother's eye as in the novel l984). In my reflection as I walked around, I was reminded of our own logo as Redemptorists, where this eye refers to Jeremiah 1:11. It is supposed to be the eye that makes us able to see "the signs of the times" long before others see them.

First major stop of my pilgrimage is to visit the

Suprema dela Ciudad Mistica de Dios, Inc. Fortunately, the Suprema - Nanay Isabela Suarez - was around to receive Allan, Pepay and myself.

Suprema dela Ciudad Mistica de Dios, Inc. Fortunately, the Suprema - Nanay Isabela Suarez - was around to receive Allan, Pepay and myself.The gate of the samahan's compound is quite dramatic. It towers to about more than 70 feet, the equivalent of a 12-storey building, dwarfing people who pose for photographs. A flag, two crisscrossed swords and fire coming out of two giant pots are the symbols on top of the gate. The gate itself is plastered with colorful flags of all nations in the world. At the bottom on both sides of the gate are angels, big birds and jars. It is quite a sight!

Inside the compound is the big house where the Suprema lives, lines of dormitories used as lodging for those who need shelter on permanent and temporary basis and the church where the members gather to pray in the mornings and evenings. The Suprema, Nanay Isabel, was most solicitous and hospitable to our small group. We were immediately asked to sit in the big receiving room and served merienda. She was not well and was going to see her doctor in Lucena City the following day (she has problems with her stomach). However, she still sat down with us and was willing to have a conversation until we run out of questions to ask.

I actually began by just asking the simple question: how did your samahan arose? Having been "interviewed" a thousand times, she could tell their story with eyes closed and her command of the Quezon Tagalog was remarkable as one could tell by the richness of her vocabulary. There was hardly any English word that was uttered. I only interrupted where I needed to be sure about the facts or didn't immediately catch what she meant by the words she said. But no amount of interruption could disturb the flow of her narrative. She was actually reciting the epic story of their samahan from her heart.

It began with the birth of their Foundress with the name Maria who when she was born from her mother's womb was inside some kind of an "egg" on August 12 many moons ago. A trusted man was asked to throw this "egg" away. However, he couldn't do it and eventually returned it to where it came from three days later. There and then, someone broke the egg. Lo and behold, there was a little girl inside the egg. This is why August 15 is a big day for the samahan and on this day is their yearly celebration that draws the participation of members from far and near. The Suprema claims that they have about 50, 000 current members spread throughout the archipelago.

Given this "mysterious and enchanted" (she used the term mahiwaga) beginnings, the Foundress would manifest extraordinary actions since she was three. Later in her life, she reached Mt. Banahaw and it was here that the samahan was established. After she died, other women were appointed supremas. (Nanay Isabel said that the samahan do not discrimate against men who could also be appointed as Supremo; however, leadership of the samahan has always been with women until today). Since its beginnings, they have had women priests in the samahan who are tasked with officiating their liturgical celebrations. (Again, men could be priests, but most priests in the samahan have been women). Priests do not necessarily have to be celibates, but Nanay Isabel chose not to marry.

She took over as Suprema when she was 22 years old again many moons ago. (One finds it difficult to guess her age today as she has such a serene face; except for her hunched back, one would think she is only in her late fifties). She was in school then and had wanted to proceed to Medicine. Despite the strong exhortations of her father - who served as guardian to the samahan - and the elders of the association who were unanimous in choosing her as Suprema, she refused and continued to live in Manila hoping to become a doctor. Then she got sick and for 20 days she was confined to a hospital where the doctor could not diagnose her with an illness.

Ultimately, her father visited Nanay Isabel in the hospital and did a healing session. Slowly, she got well after realizing that her illness was connected to her refusal to become the Suprema. She left the hospital with a resolve: she was going to accept the samahan's offer to be their Suprema.

It has not been easy for her to look after the needs of their members, run the shrine and lodging places and manage all the samahan's properties. The heavy responsibilities have taken their toll and today she has a heart problem. One could tell she is a hands-on CEO of the association; everyone in the compound all defer to her when one has a request or a question. If she is around and is well, she will be the one to entertain guests and do so without rushing.

One word that fascinated me during our conversation was her use of the word - Mistica. She herself translated the word to "mahiwaga" in Tagalog. One could tell that mahiwaga has such depth of meaning that would come very close to the etymological meaning of the English word -"mystical". I doubted if Nanay Isabel used the word mahiwaga as we do today which is bereft of the deep nuances of her own usage of the word.

For students of Spirituality - as an academic discipline - interested in indigenous mystical practices of our ancestors, here in the samahan one is afforded a glimpse into what could be one model or lived experience of mysticism that goes a long way back to our pre-colonial era. While listening to Nanay Isabel, I was conscious of a deep desire: that there would be serious Filipino scholars who would pursue this type of research as it would be most helpful in rediscovering our very deep sense of the divine as well as the roots of our own indigenous spirituality.

As an attempt to have some insights into what is the mistica of the samahan, I returned that afternoon to be "immersed" in the solitude atmosphere of the compound. I was also invited by Nanay Isabel to join their evening prayer inside their church. There was a slight drizzle late that afternoon, so I just sat still at the big house's veranda. There was hardly anyone around so I enjoyed the silence of that hour. To my delight Nanay Isabel joined me and we sat in this long bench the length of which is an entire tree.

We could see the gate and so I asked her for the meanings of the symbols attached to this gate. The crisscrossing swords are not supposed to mean anything violent or war-like; instead, holding the swords is akin to an effort to struggle against sin which, in their teachings, refer not just to personal sin but social sin as in mga kasamaan sa mundo (evils in the world). The fire symbol bursting out of the giant pots are the fire from the kalooban that lights our paths. The flags of all nations suggest that the samahan's mission cover the entire world. And the angels are guardians for human beings.

The samahan members guard over the welfare of one another. Staying in the dormitory in Sta. Lucia are families displaced by the mudslides and floods that affected Infanta and Real recently. While waiting for full rehabilitation, they are staying here and their needs are responded to by the samahan.

I joined them at the Evening Prayer where 14 women, 6 men and three children gathered along with the prayer leader (a woman who knelt all throughout the more than one hour session) and Nanay Isabel (who sat in what looked like the Bishop's chair, but placed not at the altar but among the people). The men were on the right side and the women and children were at the center and the left sides.

The symbols on the altar easily attract the eye for the colors are vivid and the lines and textures of all its constitute elements are quite sharp and well-silhoutted. The altar's "boundaries" are what appears to be a huge pair of angel's wings placed strategically at both sides. Those that can easily be seen and read from a distance are the words: At the left - Pag-ibig sa Dios, Pananampalataya, Gawa at Pag-asa and Tiyaga (Love of God, Belief, Action and Hope and Industriousness). Above these words are the Roman Numbers for the Ten Commandments. At the right - Kalinisan, Katwiran, Kaliwanagan, Katotohan, Kababaan ng Kalooban and Pagtitiis (Cleanliness, Righteousness, Being Englightened, Truth, Humility and Suffering).

Above these words is a big heart with a cross at the top and on it the words - Aral ni Jesus (Jesus's teaching). There are plastic flowers all around the altar space and candles lighted at the center. During the prayers, a woman would offer incense. The prayers are spoken, chanted and sung. The singing was quite remarkable as the congregation blended their voices; with such good acoustics, the voices are strikingly clear and very pleasant to the ears. I thought: this was how our ancestors sang or chanted their prayers (at least the Tagalog ancestors); the music was most distinct, quite different from the kind of music that Tagalog liturgical songs have today.

I could not help but be struck by the irony of it all. Here was an indigenous model of a genuine Base Ecclesial Community in prayer (whose members also insist on showing through gawa - actions and deeds - their pananampalataya or belief in God). Here is where the Filipinos have truly "inculturated" not just their liturgy but the very essense of their faith. Here was where the believers celebrated their history as a nation and expressed their genuine cultural identity. Here is a religious ceremony in a mystical site where the language, the music, the symbols, all that which are linked together, manifest nationhood (understood as genuine solidarity in community) but also being Church. Long before Vatican II, long before PCP II, the members of this samahan were already practising theologico-pastoral terms such as inculturation, liberation theology, BEC, preferential option for the poor and the like. All throughout this time I kept on asking myself: how is the Local Catholic Church dealing (or inter-faith dialoguing) with samahans such as that of Suprema Isabel. (I should have gone to talk to the parish priest, but I intuited that it would only be a source of frustration so I didn't go see him. If I am able to return there, I really should).

Returning home after the Evening Prayer, I could sense the enchantment of this place. The rain had stopped and so the walk was quite pleasant as the climate turned cold. There were fireflies everywhere, reminding me of Kulaman. Despite the presence of the military headquarter, I felt no fear and did not have any sense of foreboding as in many militarized areas of Mindanao. There were very few street lights which made some of the streets quite dark but I knew I would be safe; the spirits' presence was quite palpable.

That morning of August 21 after our talk with Nanay Isabel, Allan toured me around my first pamuemuesto. This was the route towards the river. Fortunately, the local folks have cemented the trail, so despite the rains, it was not very difficult to follow the pilgrimage route. This included the stairway to take us down to the stream below. Pepay had to leave us since she had a meeting in Sariaya (she works as community organizer of the Luntiang Alyansa sa Mt. Banahaw). A group of students from a college in Manila came in the morning for a field trip and, thankfully, they left early leaving the few of us who were intent on having a pilgrimage. The pamuemuesto meant stopping at the various shrines within the pilgrimage route, lighting a candle and saying a prayer to the saint assigned to this spot. There were more than 200 steps of this staircase from the top of the hill down to where the small river flows. The Sta. Lucia waterfalls bring its waters down to this river.

Down at the bottom are huge boulders on which statues of saints are placed. On this huge one are the statues of our Lady of Lourdes and Bernadette as well as that of the Sagrada Pamilya.

A very devout male pilgrim was sitting on a big rock facing this boulder where candles were burning as he meditated. When he stood up, one could tell that he was physically challenged and could have come to pray to make a panata so he could get well. After his prayers, he stood up and took a swim in the river.

A very devout male pilgrim was sitting on a big rock facing this boulder where candles were burning as he meditated. When he stood up, one could tell that he was physically challenged and could have come to pray to make a panata so he could get well. After his prayers, he stood up and took a swim in the river.Unfortunately, there are those who come to this place not as pilgrims but to have fun while swimming in the river. These include the local boys. Allan mentioned to me that when he came during one Holy Week the place was so crowded. And people were quite noisy as they were eating, swimming, chatting and going on a picnic. Meanwhile they throw their garbage anywhere including cigarette butts, candy wrappers, the sachets of shampoos and other non-degradable garbage turning this spot in Mt. Banahaw into a dirty spot.

As Mt. Banahaw is considered a place for healing, the local herbs are aplenty and are sold in the various small stores spread all over Sta. Lucia. One could see barks of trees, leaves, limestones being displayed and sold for their medicinal value. Some of these find their way to Quiapo and other outlets for herbal medicine and the like.

The following morning, I went through my second pamuemuesto. This time my guide was Eddie Bagtas, originally from Malabon but has lived in Mt. Banahaw in the past two decades. He acts as a pamuemuesto guide for the pilgrims; he claims the best time is the summer months, especially the Holy Week,when thousands of people find their way to this holy mountain. During the raining months such as August, his schedule is not too hectic. He is already quite knowledgeable as to the legends, stories and significance of the sites of Mt. Banahaw. As he explains these to the pilgrim, one is face to face with a local historian-theologian, since he not only tells stories within the history of Mt. Banahaw but also theologize on these events.

In this second route, one goes up the steep surface of Mt. Banahaw which means manuevering through rocks and limestones, moss-covered trails and bushes. Along the route one is confronted with diffrent kinds of caves which have been turned into shrines of the likes of Mary in her different titles, the Sto. Nino, St. Francis of Assissi, Peter and Paul and others. There were a few pilgrims we met at these puestos who lighted candles, stopped for meditation or read from their prayer books.

The most impressive was that of Ina ng Awa (Mother of Mercy). Eddie told me that on Sundays this place was filled with people as they pay homage to Our Lady as well as offer their prayers to her. The most striking element of this puesto is the big rock at the entrance of this shallow cave. The rock is in the shape of a huge heart and is kept in place by other rocks. Eddie said that despite so many earthquakes in the past, this rock remains firmly enconsed. It hangs up there on the ceiling of the cave, serving as a sentinel for the pilgrim, reminding the pilgrim of Our Lady's big heart of mercy. In fact, if one's eye can see formations on the rock, there is a silhoutte of a mother and child embosed on the surface of the heart-rock making the sight doubly mystical.

When Eddie told me that this was the shrine of Ina ng Awa, I intuited that inside the cave there would be an icon of Our Mother of Perpetual Help. I was right, in fact there were two of such icons: one that was already faded and one that is relatively new with its bright colors. There is also a picture of the Immaculate Heart of Mary and a plastic Sto. Nino. Eddie and I stayed longest in this shrine as I collected my thoughts, as I remembered family, confreres and friends needing help and as I prayed for my own sabbatical intentions.

The rest of the pamuemuesto brought us further up the slopes of Mt. Banahaw. The last puesto had jars filled with water from the spring coming out of Mt. Banahaw, a refreshing drink for the tired pilgrim. One also notices these semi-permanent structures along the route. There are actually some houses that have been built further down. But as one goes up, one sees all these structures which are empty during the rainy months. According to Eddie, these tents are filled with pilgrims who stay for days and weeks in the summer serving as their temporary abode while visiting Mt. Banahaw. During my visit, they seemed like abandoned huts of some hamletted villages.

After this pamuemuesto, I said goodbye to Eddie and I proceeded to Kinabuhayan to have a visit to the shrine of Tres Personas Solo Dios. Kinabuhayan is around 5 kms. from Sta. Lucia and one climbs steadily the slope of Mt. Banahaw to reach this adjacent barangay. I walked from Sta. Lucia to Kinabuhayan as I thought it was the more natural way for a pilgrim to reach this place. It took about thirty minutes to reach the site of this other popularly known samahan in Mt. Banahaw.

It was a quiet day and I was the only visitor. I saw immediately the white-painted statue of the Samahan Persona Solo Dios founder, Mr. Ilustre who originated from Bantayan Is. in Cebu. I sat there for a while and contemplated the symbols of this spot which serves as both shrine site and stage. There was a huge dove at the top, on the background is painted the name of the samahan and when it was founded. A slight drizzle fel and I heard the rustle of the wind across the leaves of the tall trees - narra, mahogany and the like - surrounding the shrine. After the quiet meditation, I went to the house beside the church to inquire if I could enter the church. There were women who were cleaning and washing dishes. I asked to be allowed to enter the church and one of the young girls opened the door of the church. Inside, I was immediately confronted with the image of the altar which has appeared in many a historical books, including Rey Ileto's Pasyon and Revolution.

It is the image of the Solo Dios (which is at the top of the blue triangle) hovering over three figures who all have the face of Jesus Christ (long hair, beard and all). But they are the God the Father, the Spirit and the Son. A dove figure is between the white-bearded figure at the top and the one who is the center of the three figures. Below the painted three figures is the statue of the three figures, providing some kind of a repetition of the same image as well as providing a sense of depth to the 3 figures. On both sides of the three figures are two angels. There are also other symbols on both sides of the backdrop including an ear, a hand writing, a judgement tableau, a figure that could be Mary and a prophet figure. It is, indeed, a picture with a rich imagery, no wonder it's been used as illustration in many history books.

I sat there quietly inside the church for some time to contemplate the image on the altar. It was possible to appreciate it at its different layers of meanings, as well as its aesthetics. It has a very distinct Filipino texture and design - a lot of putting together of signs and symbols and using bright primary colors. The paint used is the one that one can ordinarily buy in a hardware shop. The drawings manifest the rich popular religiosity tradition which incorporates numerology, komiks type of illustration and a sense of pang-fiesta pageantry.

In short, truly an art form evolving out of the masa. However, there are many nuances of meanings in this whole art illustration if one were to include the plastic flowers, the candles and other artifacts. Filipino religiosity offers the element of sensual vision, touch, symmetry of lines and a child-like simplicity.

In short, truly an art form evolving out of the masa. However, there are many nuances of meanings in this whole art illustration if one were to include the plastic flowers, the candles and other artifacts. Filipino religiosity offers the element of sensual vision, touch, symmetry of lines and a child-like simplicity.After I left the church, I chatted a while with Jose Illustre, a son of the Founder. He had no major preoccupations that day so he was taking it easy. He was outside when I exited the church and we chatted while he smoke a cigarette. He told me the story of how his father founded this samahan beginning with his enlightenment in Bantayan and the subsequent departure for Mt. Banahaw. He also explained their matriarchal leanings: all their "obispa" and "pari" were women, they have always been governed by women, those who were ordained necessarily had to opt for celibacy. He said that there were more women priests in Tres Personas compared to La Ciudad Mistica. He invited me to their annual fiesta on August 27 when three more women will be ordained to the priesthood. They go through "formation" under the obispa who gives them lessons.

When I asked them how many they were in this samahan, he said that they speak in terms of balangays (clusters of families) and as of the moment, they have 71 balangays spread across the country with most of them being in Luzon. Most of those in Kinabuhian are members of their samahan; others live in various parts of the country. Jose thought that things were fine with them; besides they have no aspiration to be rich. Mt. Banahaw has been good for the samahan and they certainly have done their best to protect Mt. Banahaw by looking after the trees, the springs and stream and the soil. He laments, however, that today's pilgrims are no longer as devout as the ones before and he is glad with the DENR's action to ban parts of the mountain to outsiders.

After my conversation with Jose, I went down to the pamuemuestohan at the back of the church. There is a stairway from the base of the church down to where the spring is from out of which flows waters that merge with a nearby stream.

After my conversation with Jose, I went down to the pamuemuestohan at the back of the church. There is a stairway from the base of the church down to where the spring is from out of which flows waters that merge with a nearby stream.The water sprouting out from the spring is considered holy water and it is known for its miraculous cures. Here sick people take a shower for healing purposes. I drank from the spring and felt relief from the humid heat. I also blessed myself with the crystal clear water.

As one walks through stones

and boulders gathered all over the riverbed, one notices the various puestos by the riverbanks. Here one sees a statue of Our Lady of Lourdes, one of a seated Sacred Heart (which has been hit by falling debris) and crosses. Here pilgrims place their lighted candles and pause to pray for their intentions.

and boulders gathered all over the riverbed, one notices the various puestos by the riverbanks. Here one sees a statue of Our Lady of Lourdes, one of a seated Sacred Heart (which has been hit by falling debris) and crosses. Here pilgrims place their lighted candles and pause to pray for their intentions.

Before noon, I decided to exit out of Kinabuhayan.

I walked back to Sta. Lucia. Along the way, one can gaze at one of the peaks of Mt. Banahaw which was wrapped in mist despite the noonday sun. One good view is from the elementary school campus near the gateway of the barangay. It was a short visit to this village, but a sweet one; easy and cool, delightful and envigorating.

I walked back to Sta. Lucia. Along the way, one can gaze at one of the peaks of Mt. Banahaw which was wrapped in mist despite the noonday sun. One good view is from the elementary school campus near the gateway of the barangay. It was a short visit to this village, but a sweet one; easy and cool, delightful and envigorating.That afternoon, I said goodbye to my host - the Mendoza family - whom I profusely thanked for their hospitality. I told them I was on a search for a shrine honoring Hermano Poli (or Apolinario dela Cruz), the legendary young hero (he died at age 26) whose life and heroism - especially connected with founding the Confradia de San Jose (covered lengthily by Ileto's book) - helped to inspire the setting up of the revolutionary Katipunan. If not for the events that took place in l841, I would have wished to see his graveyard. It seemed impossible to look for his graveyard considering the circumstances surrounding his death. Once captured by the Spanish forces after a battle with Tagalog rebels, they chopped off his head. Pierced with a bamboo, the head was stuck to a ground in front of his family home in Lukban, Quezon. The different parts of his body were also chopped, pierced with bamboo and placed at strategic sites of his hometown "to warn the people not to follow his revolutionary example".

After travelling for close to two hours from Sta. Lucia in Dolores to Lukban, Quezon (involving two jeepneys and a bus), I found the historical shrine at his home village in Sitio Pandak, Lukban. The National Historical Commission had carved out a space, built a monument in his honor - a more than life-sized bust painted to gold - and planted pomelo trees, San Francisco

and other red-colored plants to encircle the monument. The plants chosen are well-inspired as their dominant color is red. Red as the blood that Hermano Puli shed for the sake of his ka-bayan, long before the bayan ever became a construct in the minds of those who populated these islands, long before we could think of one another as kababayans.

Since I was in the neighborhood I also played the role of a tourist. I walked on foot around the poblacion of Lukban impressed with how the local folks have built and maintained a solid statue in honor of Gat Jose Rizal, an illustado building beside the statue and a more than a century-old church. Later I took a ride to nearby Tayabas and went to see its basilica.

The churches of Lukban and Tayabas are, indeed, impressive with their antiquity, architectural style and appearances both from the outside and inside. But - no offense please to those who build and continue to maintain these edifices - but they leave me cold after having gone through the churches and puestos of Mt. Banahaw. I sat inside these churches to do meditation but my mind remained shallow and my heart could not find its center. Something was missing: could my soul feel like a stranger in this alien and alienated religious space?

Or was I just too tired after the three days of my intense sojourn?

As I travelled back to Manila and while the bus meandered through the Province of Quezon, I could see snippets of Mt. Banahaw gazing my way. They are a haunting sight because no one leaves Mt. Banahaw remaining the same kind of person before one's pilgrimage to this holy mountain, this enchanted spot.

I could tell that I had gained new insights into my history as Filipino while being affirmed in my Pinoy identity. I sensed a deeper communion with the ancestors who had simply wished that they be set free so that they could simply live as people with dignity. Since that was not possible with the oppressive colonial masters, they knew the only way to be free was to fight for that freedom and they persisted until their heads were chopped off.

I knew that something stirred deep in my soul because of this pilgrimage. Once again, but this time after facing the lead agents - like Nanay Isabel - up close and personal, I am impressed with how the simple, poor people of Mt. Banahaw had prefigured many things we now take for granted in the Catholic Church because of Vatican II in the l960s, the MSPC in the l970s-80s and PCP II in the 1990s.

Their churches were always locally-based; they've had BECs long before such ecclesial communities arose in Latin America, especially in Brazil. They've always relied on the important contribution and participation of ordinary members of their pol-eco-religio-cultural associations. Their leaders never made decisions without consulting the members. They've inculturated their liturgies, celebrating the richness of the Tagalog language and their indigenous music the strains of which parallel the flow of streams and evolving symbols whose meanings could produce scholarly dissertations but areeasily understood by even the unlettered. Their theologies were always soteriologically holistic devoid of the binary oppositions of pre-Vatican II, grounded in the aspiration to be liberated from shackles of the colonial rule of an Empire, nature-based and women-centered. While our Church continue to exclude women from priesthood, their women priests have taken the center stage for almost a century already.

So, who are the truly blessed by the God we believe in?